Shooting Strangers

I recently posted this Guardian commentary on my personal facebook and caused quite a debate. It is something I have thought about on many occasions and so I thought I would explore the matter in more detail here.

In her article Nell Frizzell discussed the (admittedly puerile and often offensive) practice of photographing strangers on public transport and posting these images to ‘blogs, often as an object of derision. She notes the harm this may cause to the subjects, and also the fact that due to advertising space being sold on such ‘blogs these people have now become a commodity to gain revenue. Ultimately, she concedes that while ‘the legal issue is murkier than a dimly lit pub toilet selfie’ the moral issue surely is not, and states her belief that we should not shoot strangers in public.

I feel that Frizzel’s argument is a little naive. On a very basic level, in writing her comment she links to a number of examples, thus promoting the very posts and ‘blogs about which she shows such concern. But this is a minor issue, and perhaps inevitable.

What concerns me more is her claim that the moral issue is so black and white.

I will briefly run through the legal concerns. I do not think that they are totally transparent, but i feel that they are a fair bit clearer than Frizzell believes. In doing this I will consider the issue of harm to the subject, as well as the subject as commodity. Then I will address the moral issue, which to my mind centres around the fact that there are two people in the social relationship created by producing an image, and they both have some rights.

The law surrounding photographing a stranger can be loosely encapsulated by the basic position that in public the public arena we have no expectation to full privacy. So in the street, or if seen from the street (including your house if you do not close the curtains), your activities may be seen, and hence recorded by other people.

Now, obviously a train or bus is in no way public, it is private property to which the public have been granted access. But unlike a private members club it is, barring the right of the operator to refuse entry, open to all. You cannot expect that your activities in this place a secret to all but a select few of your chums.

Of course there are many, myself included, who are concerned by the rise of the surveillance society and this issue does sit ill with this argument to an extent, but we are not talking about the routine monitoring of a populace by someone in power, we are talking about someone taking an opportunist image.

The act of photographing a stranger can constitute harassment. In general, harassment requires repetition. There are some cases where it may not – for example if I were to I sneak up behind someone at ground level to capture an ‘upskirt’ this could clearly and rightly be defined as sexual harassment. But the defining factor here is that the person concerned would have an expectation that, although they are in public, the public do not have a reasonable right to take picture of their gusset. Similarly, if I took images of someone and they asked me to stop, but I continued to shove a 10mm lens six inches from their face I have repeated an action which they have informed me they do not appreciate. This, I think, is quite clear, as far as it can be given the fact that (like many things) there is no point by point description in law about every action which is ‘harassment’.

Where I concede that the law (and indeed morals) may become a little more clouded is the issue of the subject becoming a commodity. Recently a case has been heard surrounding the you tube hit ‘technoviking’. The subject of this video, filmed by an amateur film-maker at the Berlin Fuckparade successfully sued the videographer for ‘personality rights’ and hence the income generated by You Tube adverts. I am in two minds about this. I agree it may be galling if someone makes money from your ‘personality’. But at the same time I would not like this to set a precedent where I would feel unable to shoot an image of someone for fear they may plunge me into financial ruin.

In general, the accepted wisdom (though I confess I do not know where, if anywhere, this is defined in law) is that if you use an image for editorial purposes you do not need a model release. But if that image is used for advertising then you do. So if, for example, I go to Glastonbury and take an image which I sell to a music magazine for an article on festival culture then that is fine. But if I sell it to the company who made the subject’s jacket to advertise that product I should have a release from the model. In this situation they are putting their face to the product. In general, most photographic stock agencies require a release anyway.

So this does leave a grey area if I post an image on a website where I have signed up to a revenue sharing scheme and money is made from adverts next to that image. Should the subject receive some of that cash? I will give you an example, in order to show the futility of this idea. I am in a demonstration, and a journalist takes an image of me and my placard fighting for lower university fees and sells that to the Daily Mail who denounce me as a leftie bringing down the state. Do I get revenue from the advert for payday loans on the opposite spread? I certainly have not put my name to the newspaper’s politics, nor the product, but that editorial shot is making income from advertising. Does it differ if the image is in the Guardian, I am venerated as a campaigner for good, and the advert is for an ethical bank? How do you manage a law that upholds my rights in one place but not another?

So this brings me in a roundabout way to the rights of the photographer and the subject.

I vociferously uphold my rights as a photographer to take an image of a member of the public in a public place and do what I want with that image to which I hold the copyright. I do not use images to deride anyone (ok, I might do if I shot an EDL rally), I use images to create a piece of art, or a piece of documentary data.

My partner challenged me on this, basically saying should my right as a photographer to make an artistic image supersede the right of the subject to privacy? Though let’s remember that this right does not exist automatically, as rights are not inherent, they are given in any functional sense of the word and no right to privacy has been given here.

My point here is that removing my right to photograph a stranger in public potentially does two things. It takes the ownership of the public arena away from the public and into the hands of the powerful, and ultimately threatens my right to take any image in public.

I want to discuss the second of these in some more detail.

My argument revolves around the simple premise question of ‘when am i actually taking a picture of the person?’ In some cases this will be clear, the person is without any doubt the subject of the image. But in many other cases it is not. If i take a picture of a street with some people in it, are they the subject? In some shots the street might be the subject, but the figures (who may not even be identifiable) are a focal point without which the shot would not work. So, do we set a limit of 50% of the frame? 25%? To be safe can I not take an image if anyone appears in it, even if they are a mere blip of colour? What if i have spent 2 hours waiting for people to get out of the bloody way so I can shoot the landscape shot I am after unimpeded? Can I take the shot and clone them out in photoshop later?

Here we have a really difficult legal definition to create, and the moral position suddenly becomes more blurred as it threatens to take away far more of my rights than the simple one to shoot a person in public.

And then of course, this means that there can be no news reporting of anything involving people. Unless we allow some people to take pictures. Whom do we allow? The police? Members of the national union of journalists? Isn’t citizen journalism an important part of taking the power back?

I respect entirely the point that Nell Frizzell is attempting to make. But her suggestion opens up a far larger can of worms than it would close.

Frizzell suggests that she may be a ‘ludicrous old libertarian’, but I wonder if on deeper thought she could see that the results of her suggestion would in fact be entirely the opposite.

There are various laws which can protect someone if an image (or the use of that image) causes them harm. Again one can comment that this is ‘shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted’ and I agree this may sometimes be the case. But short of a draconian ban on any candid image with a human subject, which I hope I have shown is practically impossible to define, it is what we have. Of course, it is impossible to assess harm – an image showing a seemingly unrecognisable person may provide enough evidence to position someone in a certain place at a certain time giving that knowledge to the police, or to a violent ex partner. but we have to risk assess this when we shoot and publish images. There is no answer which applies to every case.

And how do you police intent. I may take a shot of a crowd at a festival, but who is to say I did not do it so I can crop down to the girl with the large breasts and post that for misogynistic comment on a porn forum? Yes, these may point back to Frizzel’s suggestion we simply avpid taking the shot at all, but once again the cost of that to is to culture as a whole. A world where no depictions of people are lawful, or those that are lawful are controlled by a set few people- is, I think, a greater social harm than the risk that one person may be inadvertently harmed. This is almost elementary ethics.

You don’t see cars banned because some people drive immoderately.

As photographers the best we can do is respect our subjects and ensure that our values are sound. I shoot a lot in clubs, and it is not uncommon that someone will ask me to take down an image – maybe even one that they nagged me to take in the first place – because in the cold light of day they decide it is not safe for their boss to stumble upon. I do this with good grace. Every time.

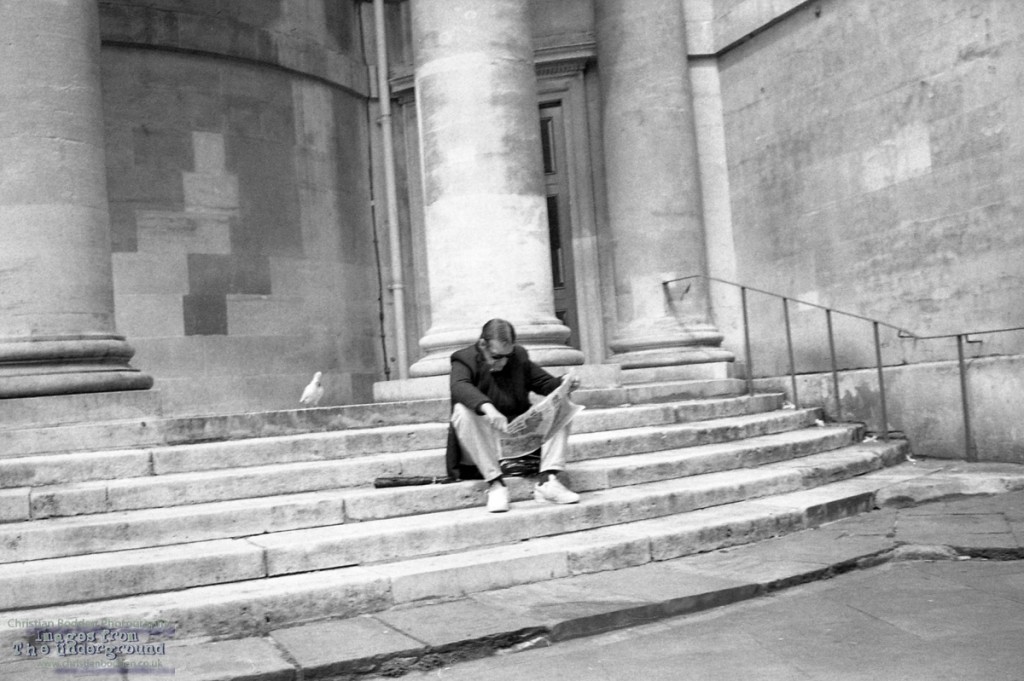

This is an issue which will probably never be solved. And that is where Frizzell is entirely wrong – the moral dilemma is not in any way clear. I have illustrated this post with some candid street images, that as part of my Saturated Imagery project I have shot to film on basic point and shoot cameras. I will allow you to judge for yourselves.